Help-seeking Behavior, Goal Orientation, and GNS Theory in Interactive Literature

Introduction

Anyone who has played in, run, or even watched a live action role-playing game (LARP) knows that LARPs in general and interactive literature LARPs specifically are not like other kinds of games. They are multi-player games where players each play at their own rate and where the mechanical aspects of the game are deliberately undergirded by social interactions. Interactive literature also has a natural help structure in the form of the game masters, who arbitrate disputes, provide information, and clarify confusion for the players.

This paper presents a study of help-seeking behavior by role-players at interactive literature events. The study measures how much help was sought, the type of help that was sought, and from whom. Also examined is how a player’s goal orientation affects their help-seeking or enjoyment of play.

Studying help-seeking behavior in interactive literature not only helps us understand more about how players get enjoyment out of games, but can inform our understanding of how people might seek help in other similar social situations. For example, as K–12 education explores ways to allow students to work at their own pace, classroom help-seeking can come to look more and more like help-seeking in interactive literature. Indeed, as games become increasingly popular in education due to their ability to allow educators to tap into the motivational benefits of play, studying help-seeking behavior in a low-risk, game-like environment with a flexible, adaptable help structure (such as interactive literature) could help in designing effective, pre-determined scaffolds for learning in educational games.

Help-seeking in Interactive Literature

To understand how and why a player might seek help during play, we need to consider (1) the kind of helper the game masters (GMs) are, (2) what player characteristics might predispose a player to seek help or not, and (3) what kinds of help might be sought. In regard to the latter, a taxonomy of player-initiated interactions was developed (see tables 1 & 2).

In comparison to educational helpers, GMs occupy a space somewhere between tutor and peer-tutor. Tutors typically have more domain information than their tutee and also have some amount of authority over their tutee. Peer-tutors are seen as having roughly the same social standing as the tutee, and do and are not expected to have significantly more domain information. GMs are the peers of the players, but also have more and privileged information about the game and often are responsible for logistical aspects of the game such as space and safety coordination.

Not all players need the same amount of help. Different players will need different levels of help depending on the game-play conditions they encounter, and this can affect their thinking as they become aware of that need (Aleven, Stahl and Schworm). Some players will be more prone to seeking help than others, possibly due to their ability to perceive their own need for help, or because of some characteristic of that player which affects their decision to seek help. One characteristic that might impact this decision is the player’s experience level—research into help-seeking in learning environments has found that prior knowledge affects outcomes (Wood and Wood).

A player’s decision to seek help may also be affected by their goal orientation. Goal orientation can be described as how motivated an individual is by achieving certain goals. Goals can be divided into two categories: performance goals and mastery goals (Dweck and Elliott). An individual motivated by performance goals is trying to achieve a certain measurement, either for their own intrinsic reason, or to be looked upon favorably by others. An individual motivated by mastery goals is trying to improve at the skill regardless of measurements—the activity is its own reward. Performance goals are further split into performance-approach goals and performance-avoidance goals. Performanc-approach goals are focused on the achievement of a reward for showing success at a measurement. Performance-avoidance goals are focused on not failing at a measurement (Elliot and Church).

If we know a player’s experience level and their goal orientation, might we be able to predict how much help they might seek from their GM, and of what kind?

GNS Theory

The question of why humans enjoy a particular activity is a thorny one, part cultural, part psychological, and part practical—how can we make something more fun? Over the years a string of theories and constructs have been formed to help tease apart the qualities and aspects of role-playing that people find engaging. While there has been a recent increase in activity, historically little scholarly work has been done on theories of role-playing the context of games, with the marked exception of Fine’s sociological analysis of role-playing games, Shared Fantasy: Role-playing Games as Social Worlds (Fine). Currently, the most commonly accepted and referenced role-playing theory for LARPs is GNS or Gamer-Narrativist-Simulationist.

GNS has its roots in a previous model called the Threefold Way (coined by Mary Kuhner in 1997 on the internet forum rec.games.frp.advocacy)—which attempted to classify the motivations of gamers. It describes three stances that a game master might bring to a game decision based on the relative value they place on game, simulation, and drama (Mason). The GNS model restates the trichotomy as having gamist, narrativist and simulationist values, and where the player’s interactions support each value independently. The gamist value rejects the popular stance that one cannot win a role-playing game. The narrativist sees their character as a part of the broader story. The simulationist places value in seeing how a situation would play out as realistically as possible, and as such is the most prone to role-taking (Coutu; Haas).

While several versions and children of the GNS model exist, including the GENder model and The Big Model, GNS remains at the heart of most modern theories of role-playing.

Research Questions

Prior to designing a study, research questions were framed based on a simple model of how help-seeking and goal-orientation might interact with other elements of the game (Figure 1). The model in Figure 1 represents the hypothesis that this study is examining—essentially that help-seeking behavior is affected by a player’s goal orientation and their level of play experience; that a player’s help-seeking behavior and the social connections they have in the game play will affect the player’s overall satisfaction; and that gamer type (where the player sits in the gamist-narrativist-simulationist model) can be predicted by variance in goal orientation.

The research questions the study was designed to address are:

- Do performance-approach oriented individuals request more information through help than non-performance-approach oriented individuals?

- Provided multiple possible helpers, do help-seekers return to the same helper, or seek help from multiple sources?

- Are performance-approach oriented individuals that seek more help more satisfied by their play experience?

- Is Gamer Type (based on the gamist-narrativist-simulationist theory) predicted by a player’s goal orientation?

Method

A study of three separate interactive literature events run at Intercon (an all-LARP convention) included 85 unique participants playing 96 characters (some players played in multiple of the games studied). Each event was four hours in duration, and the participants were evenly split.

| Duration | # of GMs (helpers) | # of players | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Event 1 | 4 hrs | 3 | 33 |

| Event 2 | 4 hrs | 3 | 33 |

| Event 3 | 4 hrs | 2 | 30 |

Pre-event Survey—Goal Orientation and Experience

Approximate experience level was gathered by inquiring as to the number of events the player had previously participated in and categorizing them on a 1 to 5 scale. The scale was logarithmic, with a report score of 1 indicating they had no prior LARP experience and 5 indicating they had participated in over 150 LARPs. While not needed to measure the research questions directly, each of the nodes of the conceptual model were measured in some way, so as to build a more complete data set for future analysis.

To assess the players’ goal orientation, the pre-event survey presented them with a modified version of PALS (2000) subscales for mastery, performance-approach, and performance-avoid. Since PALS is a validated measure, the survey questions were modified only to make them applicable in the context of interactive literature.

Mastery

- I like roles that I’ll learn from even if I make a lot of mistakes.

- An important reason why I LARP is because I like to learn new things.

- I like a LARP best when it really makes me think.

- An important reason why I LARP is because I want to get better at it.

- An important reason I LARP is because I enjoy it.

- I LARP because I’m interested in it.

Performance-Approach

- I would feel really good if I were the only one who could solve the final puzzle.

- I want to do better than other players.

- I would feel successful if I did better than most of the other players.

- I’d like to show my GM that I’m better than the other players in my game.

- Doing better than other players in game is important to me.

Performance-Avoidance

- It’s very important to me that I don’t look stupid when I LARP.

- An important reason in how I play my character is so that I don’t embarrass myself.

- The reason I play the way I do is so others won’t think I’m dumb.

- One of my main goals is to avoid looking like I don’t know what I am doing.

- One reason I would not participate in an in-game activity is to avoid looking stupid.

- Pre-event Surveys were returned at a rate of 90.5% (77 of 85). Missing surveys were due to players that were late for the game.

Quantitative Field Observations: Runtime Monitoring of Help-seeking

The goal of this method was to determine the locus of help, given multiple potential helpers, and the type of help that players requested. During each game, GMs coded all player-initiated interactions (both help-seeking and non-help-seeking). Help-seeking events were coded into four categories: consultative help, validation, information seeking, and clarifying. GMs also coded four categories of non-help interactions: taking game actions, game commentary, logistical, and not game related. A single player-initiated interaction could be coded into multiple categories.

| Help-Seeking Category | Description |

|---|---|

| Consultative | The player is seeking your input or asking for your advice on what actions to take, or how to handle a situation. |

| Validation | The player is looking for a show of approval for their actions or to acknowledge how noteworthy some action of theirs was, or will be. |

| Information Seeking | The player is requesting additional information to what was provided to them previously. This would be information that is entirely new to them. Note that this is just a classification of the request—it does not matter if the information was provided or not. |

| Clarifying | The player is seeking to clarify or confirm information they already have, such as asking if the player with the nametag “Bob” is the same Bob from their background. |

| Non-Help-Seeking Category | Description |

|---|---|

| Taking Game Action | The player wants to interact with the GM in their role as representing reality in order to take some action in the game. This includes actions such as performing dangerous physical feats, interacting with the virtual contents of a room, or searching a virtual database for information. |

| Game Commentary | The player wants to talk about the game, but is not looking for a response from the GM. |

| Logistical | The player asks a question or informs the GM of a situation related to the logistics of the game. Example: “I have to leave at 6pm” |

| Not Game Related | The player wants to talk to the GM about something other than the game. |

For inter-rater reliability, the coding system was piloted with three individuals coding player help-seeking behavior (kappa = 0.56). After the event the raters discussed the discrepancies between their results, and the category descriptions were improved, and an additional category Logistical was added. Eight raters were trained using the improved category descriptors and completed the coding of a series of test cases gathered from a panel of expert GMs (kappa = 0.62).

Post-event Survey

Immediately after the event, participants completed a short survey to capture their enjoyment and satisfaction levels using a hedonic smiley scale. Post-event surveys were returned at a rate of 69.7% (67 of 96). The discrepancy between the number of pre-event surveys handed out and post-event surveys handed out was due to eleven players that participated in two games. Only one pre-event survey was collected for these players, while one post-event survey was collected for each of their games. The hedonic smiley scale was later coded into a 1–5 for analysis.

| I was satisfied with my character |  |

| My character was interesting |  |

| Others seemed to enjoy this game |  |

| I enjoyed this game |  |

| The GMs were helpful |  |

Results

A review of data sorted by variable, and a review of a histogram of each variable helped to make sense of the data and check for errors in the manual data-entry. The means and 95% confidence intervals, as determined by bootstrapping, are reported below. The mean experience level of 3.61 indicates a prior experience of approximately 60 LARPs.

| Variable | Range | Mean | 95% Confidence Interval |

|---|---|---|---|

| Experience | 1.00–5.00 | 3.61 | 3.44–3.79 |

| Performance- Approach | 1.00–4.20 | 2.47 | 2.34–2.60 |

| Performance- Avoid | 1.00–4.00 | 2.12 | 1.98–2.27 |

| Mastery | 2.84–4.84 | 4.01 | 3.92–4.09 |

| Variable | Range | Mean | 95% Confidence Interval |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Help events (per player per game) |

0.00–15.00 | 2.44 | 1.86–3.06 |

| Consultative | 0.00–3.00 | 0.44 | 0.28–0.60 |

| Validation | 0.00–5.00 | 0.33 | 0.19–0.51 |

| Information Seeking | 0.00–9.00 | 1.02 | 0.73–1.36 |

| Clarifying | 0.00–5.00 | 0.65 | 0.44–0.88 |

| Non-help events | 0.00–9.00 | 2.24 | 1.75–2.76 |

| Variable | Range | Mean | 95% Confidence Interval |

|---|---|---|---|

| Satisfied with the Character | 2.00–5.00 | 4.52 | 4.36–4.66 |

| Character was Interesting | 3.00–5.00 | 4.42 | 4.28–4.55 |

| Others Enjoyed the Game | 3.00–5.00 | 4.65 | 4.54–4.76 |

| I Enjoyed the Game | 2.00–5.00 | 4.59 | 4.44–4.74 |

| GMs were helpful | 3.00–5.00 | 4.55 | 4.42–4.67 |

Although the confidence intervals for satisfaction measures do not touch the maximum value of 5.00, they are all very close. Looking at the distribution for the values of responses (Fig. 2) to “I enjoyed the game,” shows there may be a ceiling effect on this measure. That the surveys were not anonymous (due to a need to be able analyze across measures) may lead to a bias due to self-presentation. Self-selection may be a factor—repeat players have enjoyed this type of game in the past and sign up for games they believe they will enjoy. Also, several individuals showing frustration or dissatisfaction were observed not returning or refusing to complete their post-event surveys, possibly leading to a self-selection bias towards high satisfaction rates on the post-event surveys.

Research Questions

Do performance-approach oriented individuals request more information through help?

Research on help-seeking in interactive learning environments has found that students often use on-demand help systems to achieve their goals (get correct answers) without mastering the material (Aleven and Koedinger). If learning the privileged information that the GM knows was seen as a strategic advantage to performance-approach oriented players, we would expect they would request more information than low performance approach individuals. Not only have we failed to reject the null hypothesis, but the data shows essentially no difference in information-seeking between performance-approach oriented individuals and non-performance-approach oriented individuals. Performance-approach correlates with information-seeking at r(65) = 0.019, p=0.88.

This could be because the players do not see additional information as a strategic advantage, or because they do not believe a request for the information will be fruitful—that is they may be self-monitoring their requests in order not to wear out the good will of the GM. Another possibility is that the goal the players are hoping to achieve is the approval of the GM. If that is the case then the player may be self–monitoring their requests because they see them as a risk-factor which could lead to a failure in gaining the GM’s approval. One piece of evidence that this is true would be a correlation between performance-approach orientation and validation help events (see the Other Findings section for more on this).

Provided multiple possible helpers, do help-seekers return the same helper, or seek help from multiple sources?

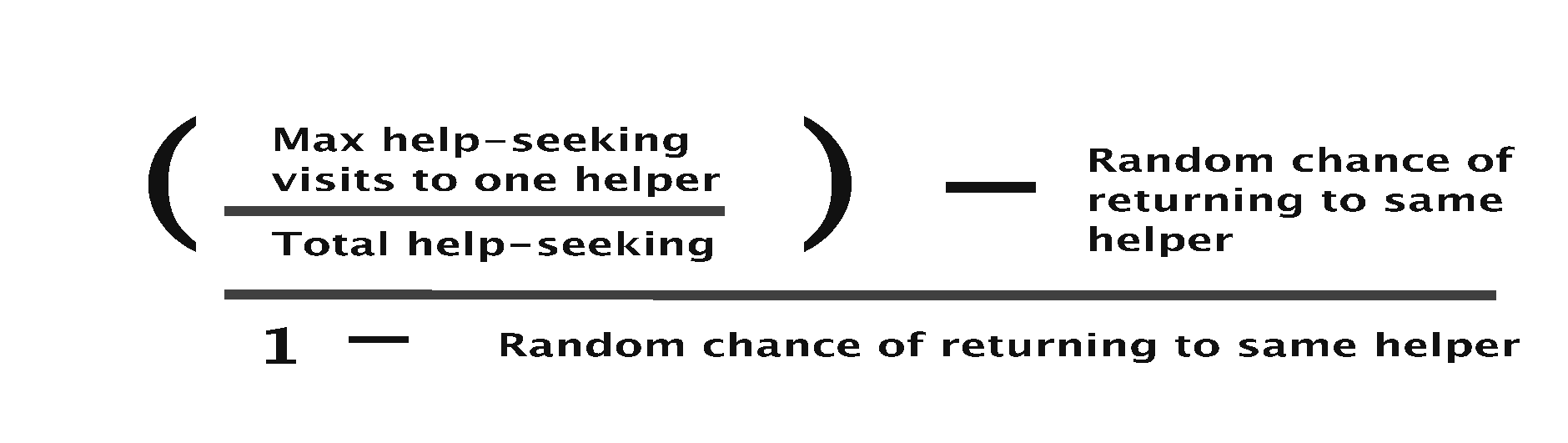

Considering only the players that asked for help at least twice in a single game (N=47), we found that 39.6% used only one helper. Using the formula below, we found that repeat help-seekers returned to the same helper 62% better than chance.

There are many possible reasons for this pattern of behavior. If a player has a successful help-seeking interaction with a helper they would have a positive meta-cognitive evaluation of the help-seeking episode. This may lead to the player strategically preferring that particular helper when they select a help-seeking strategy for a following help-seeking episode. There may also be pre-existing social bonds or social bonds that are created through the help-seeking interaction that encourage the help-seeker to return to the same helper. Finally, there may be contextual reasons included in this behavior—what we report as multiple instances of help-seeking may actually be a single line of requests dealing with the same subject, causing the player to strategically select the same helper due to the helper’s understanding of the context of prior requests.

| Variable | Mean | 95% Confidence Interval |

|---|---|---|

| Likelihood to return to previous helper | 0.622 | 0.528–0.717 |

Are performance-approach oriented individuals that seek more help more satisfied by their play experience?

Although our results do not allow us to reject the null hypothesis, the trend in the data is that performance-approach oriented individuals that seek help are less satisfied with their play experience. We looked at two populations of performance-approach oriented individuals, splitting the overall population by absolute measures (>3) and splitting the overall population based on the mean performance-approach score (>2.5). For individuals with Performance-Approach scores >3 there is a negative correlation between help-seeking and enjoyment, r(8) = -0.50, p=0.15. For individuals with Performance-Approach scores of > 2.5 there is a negative correlation between help-seeking and enjoyment, r(23) = -0.29, p= 0.16.

Although these results are not statistically reliable, the trend may indicate that, for this performance-approach oriented population, help events are generated as a result of less than ideal play. Since satisfaction scores were very high it may be that, in this case, help-seeking is more of an optimization strategy than a strategy to mitigate dissatisfaction. The player may become frustrated if they thought they had a way to achieve their goals only to fail when their help-seeking fails; frustration-aggression theory defines frustration as “a state that sets in if a goal-oriented act is delayed or thwarted (Dollard, Doob and Miller).” Frustration could be described as having high arousal and low valence (Russell), which may help explain how frustration can lead to other negative-valence emotions and reduce satisfaction scores. That is to say, that once a player starts to actively feel a negative emotion such as frustration, it will be easier for them to transition to other negative emotions, which would naturally reduce satisfaction scores.

If we consider enjoyment a measure of success for the game, we could state that players who report less enjoyment are more in need of help—they need help to succeed at enjoying the game. In that light, this trend could indicate that help-seeking in games and game-like environments may not hold to classroom findings that those who need help the most are the least likely to ask for it (Karabenick and Knapp). This trend has a significant effect size, and it may be worth collecting more data to see if we can reject the null hypothesis.

Since the question tackles the relationship between player characteristics and help-seeking events, for players that played in multiple games, we are considering the average of their help seeking events across their multiple games. Eleven of 85 players played in two games, the remainder played in only one.

Is gamer type (based on the gamist-narrativist-simulationist theory) predicted by a player’s goal orientation?

That modern role-playing theories such as the gamist-narrativist-simulationist theory (GNS) are generated amongst role-playing enthusiasts rather than from research based or academic sources has lead to many questions about the validity of the theories. Since GNS Theory considers motivational stances of role-players, one possible test of the validity of GNS Theory would be to compare it to validated measures of motivation, such as the trichotomous model of goal orientation.

A leave-one-out forward ANOVA for gamer type “gamist” generated a model that included only one variable—Performance Approach. This indicates that by measuring a player’s performance-approach goal orientation, we can predict how they will score on a measure of the gamist GNS stance. Performance-approach correlates with the gamist stance at r(78)=0.411, p=0.00. The ANOVA model included the three goal orientations as well as the player’s total experience.

The narrativist and simulationist GNS stances both correlate with mastery goal orientation. Simulationist correlates slightly more strongly at r(76)=0.444, p=0.000, and narrativist slightly more weakly at r(75)=0.408, p=0.000.

These results indicate that GNS theory stances can be predicted by at least one validated scale (PALS subscales for Goal Orientation). However, goal orientation cannot distinguish the narrativist and simulationist stances, which could mean that GNS is not a pure measure of motivation, but also includes aspects of gameplay. It is also worth noting that no GNS stance correlates with the performance-avoid orientation. While this could mean that GNS is incomplete, a more likely explanation is that GNS is a theory of a system that self-selects against performance-avoidance. After all, people who are motivated by avoidance failure are not likely to take part in a game if they feel like there is a good chance of failure.

It is also important to note that the GNS survey questions are not validated or guaranteed to accurately measure GNS stances. The GNS results are best considered as a trend which suggest that more controlled and validated measurements may be warranted.

Other Findings

An exploration of the collected data was conducted to determine the answer to follow-up questions. An attempt has been made to confine the number of additional tests to a small number in order to reduce the chance of type II errors. Included with each follow-up question is the number of tests performed in this exploration.

Is there any pattern in the kind of help sought by performance-approach oriented individuals?

This was a follow up on Research Question 1, which asks about performance-approach oriented individuals and information seeking. The natural follow-up was to ask about the other types of help-seeking. For this we did four additional tests, and found small effect sizes for Consultative and Clarifying help-events. The one type of help that performance-approach oriented individuals are slightly more likely to seek is validation, with a correlation of r(65)=0.254, p=0.038. Performance-approach oriented individuals are also more likely to initiate non-help interactions r(65)=0.249, p=0.043. That performance-approach oriented individuals sought more validation also points to the possibility that one of the goals they wish to achieve is the approval of the GM, and that other help requests are being self-monitored in order to help achieve this goal.

Does experience matter?

To examine experience in relation to goal orientation, overall help-seeking and satisfaction measures, nine additional nine tests were conducted. Experienced players tended to be mastery oriented as evidenced by a moderate correlation of r(76)=0.307, p=0.006. One likely reason for this is self-selection—players who participate in many games are likely to be those who see intrinsic value in interactive literature and who see the activity of LARPing as its own reward.

Experienced players also tended to perceive the GMs as less helpful r(51)= -0.359, p=0.008. Since this is a measure of perceived helpfulness it can be used to look at how a help-seeker evaluates the help-seeking episode (Aleven, Stahl and Schworm). If a player were to evaluate a help-seeking episode and conclude that they would have been able to succeed without help their perception of the helpfulness of the GM may decline. If these expert players are requesting help in more challenging areas it is more likely that the help provided does not satisfy their request. The data collected was only for help-seeking, not what help was given, so another possible explanation is that the GMs decided not to provide the help requested—either because there was no additional information available or because they perceived the player to be able to resolve their problem on their own.

Did seeking any particular kind of help improve a player’s enjoyment?

Help-seeking types were examined for impact on enjoyment, using six additional tests. Neither information seeking, validation, clarifying, non-help-seeking events, nor overall help-seeking had an impact on the player’s enjoyment. Consultative help, however, had a moderate negative correlation—the more a player requested consultative help, the less they enjoyed the game—r(60) = -0.390, p=0.002. Simple explanations for this are that GMs gave poor advice, or that GMs were less likely to provide this kind of help when requested. However it also may not be the act of help-seeking that results in less enjoyment, but that they both stem from another source cause. Consultative help is requested when the player is unsure of what to do, and it seems likely that players that become stuck enjoy the game less.

Implications

These results tell us not to ignore help events when looking at gameplay because, in game environments, help events can be seen as indicators that a player is struggling. While game designs should try to avoid the need for help events, attempts to prevent or regulate the use of help could cause frustration and dissatisfaction. Any game that can become aware of its players’ goal orientation should design in validations for performance-approach individuals, which this study has shown correlates with higher satisfaction levels. This validation can be thought of as a type of route confirmatory sign—confirmation that the help-seeker is on the right path. One example of this is when players use statistics in computer and console games to provide active, instant feedback that is used as a validation measure. A report of the player’s DPS or Kill Count at the end of the level is not only a summary, but also a motivational help tool. In Interactive Literature, this might be achieved by making the progress toward a goal visible to the player, or a GM proactively telling a player they are doing well. It may seem counterintuitive to disrupt immersion to communicate to the player, but for performance-approach players, it might just increase their satisfaction.

Future Study

Quantitative field observation of help-seeking in LARP can provide a unique look into both unstructured help seeking in general and into aspects of gameplay. This study has started to look at help seeking as it relates to goal orientation, locus of help, and the GNS theory of role-play, but many other possibilities for future study exist. Even just within the conceptual model hypothesis put forth in this paper, it is possible to ask how aspects of gameplay such as character social connections interact with help seeking. Might a player whose character has more connections seek less validation from the GM? Does the rate of non-help interactions predict the rate of help interaction? With little prior art in this area, additional, similar exploratory studies are warranted to help develop a model for help seeking behavior in games.

References

Aleven, V and K. R. Koedinger. “Limitations of Student Control: Do Students Know when they need help?” Proceedings of the 5th International Conference on Intelligent Tutoring Systems, ITS 2000. Ed. C. Frasson & K. VanLehn G. Gauthier. Berlin: Springer Verlag, 2000. 292-303.

Aleven, V. and K. R. Koedinger. “Investigations into Help Seeking and Learning with a Cognitive Tutor.” Papers of the AIED-2001 Workshop on Help Provision and Help Seeking in Interactive Learning Environments. Ed. R. Luckin. 2001. 47-58.

Aleven, V., et al. “Help Seeking in Interactive Learning Environments.” Review of Educational Research 73.2 (2003): 277-320.

Coutu, Walter. “Role-playing vs role-taking: An appeal for clarification.” American Sociological Review 16.2 (1951): 180–187.

Dollard, J, et al. “Frustration and Aggression.” New Haven: Yale University Press., 1939.

Dweck, C. S. and S. Elliott. “Achievement motivation.” Handbook of Child Psychology: Socialization, personality, and social development. Ed. P. Mussen. Vol. 4. NY: Wiley, 1983. 643-691.

Elliot, A. J. and M. A. Church. “A hierarchical model of approach and avoidance achievement motivation.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 72 (1997): 218–232.

Fine, Gary Alan. Shared Fantasy: Roleplaying Games as Social Worlds. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1983.

Haas, Robert Bartlett. Psychodrama and sociodrama in American education. Beacon: Beacon House. , 1949.

Karabenick, S. A. and J. R. Knapp. “Help seeking and the need for academic assistance.” Journal of Educational Psychology 80 (1988): 406-408.

Mason, Paul. “Search of the self.” Montola, Markus and Jaakko Stenros. Beyond Role and Play. Helsinki: Ropecon ry, 2004. 1 - 14.

Midgley, C., A. Kaplan and M. Middleton. “Performance-approach goals: Good for what, for whom, under what circumstances, and at what cost?” Journal of Educational Psychology 93 (2001): 77–86.

Russell, J. “Core affect and the psychological construction of emotion.” Psychological Review 110 (2003): 145–172.

Wood, H. and D. Wood. “Help seeking, learning and contingent tutoring.” Computers and Education 33 (1999): 153-169.